SELECTED

FABRICATION

STRATEGY

WEB-DESIGN

ANIMATION

SHOWCASE

GRAPHICS

DATA-VIZ

TEACHING

WRITING

ALL

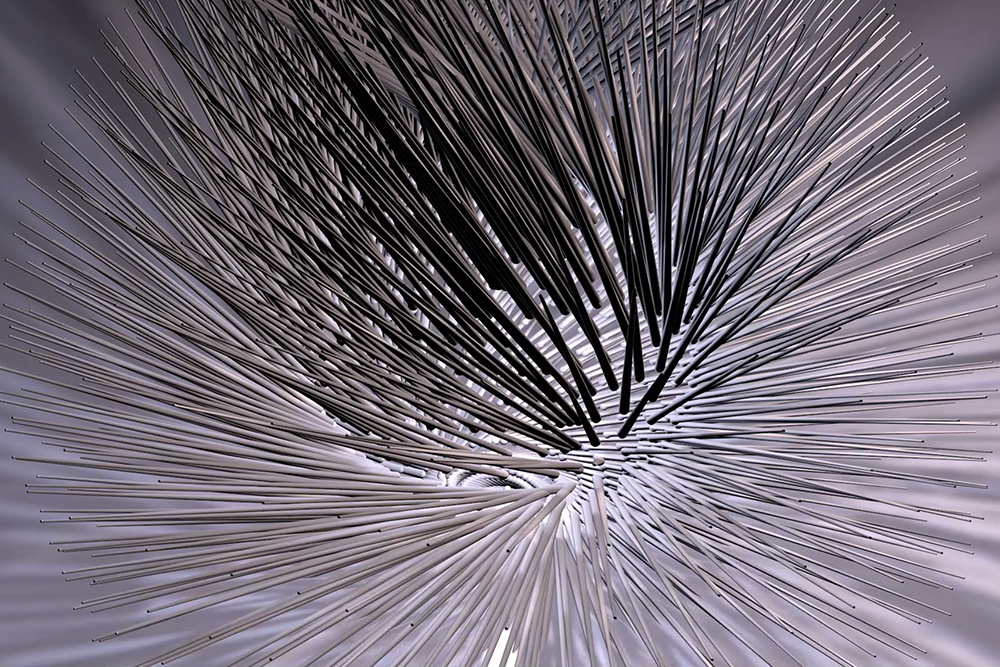

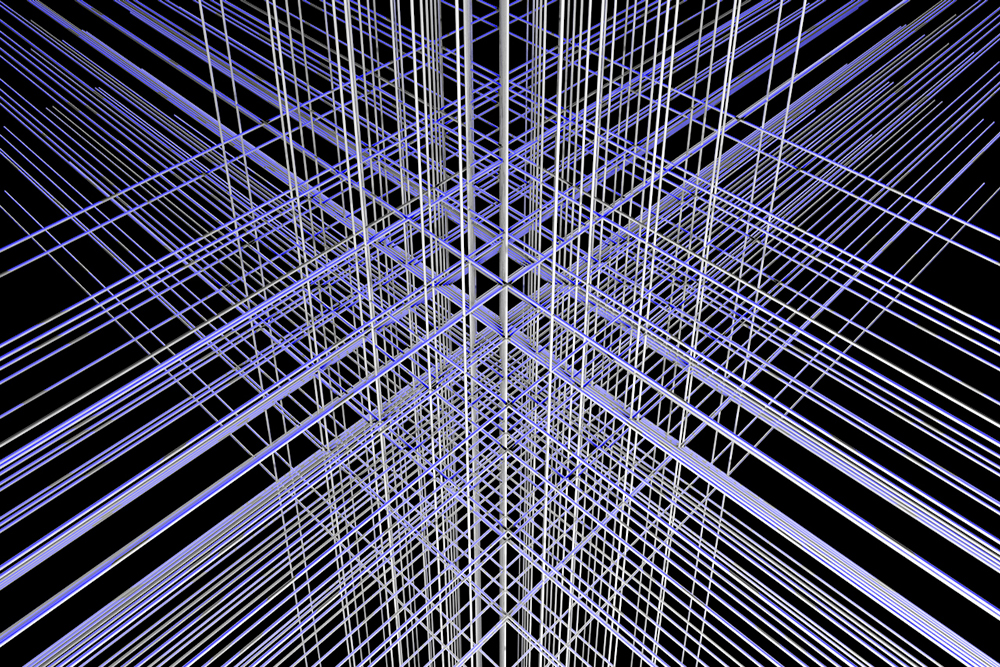

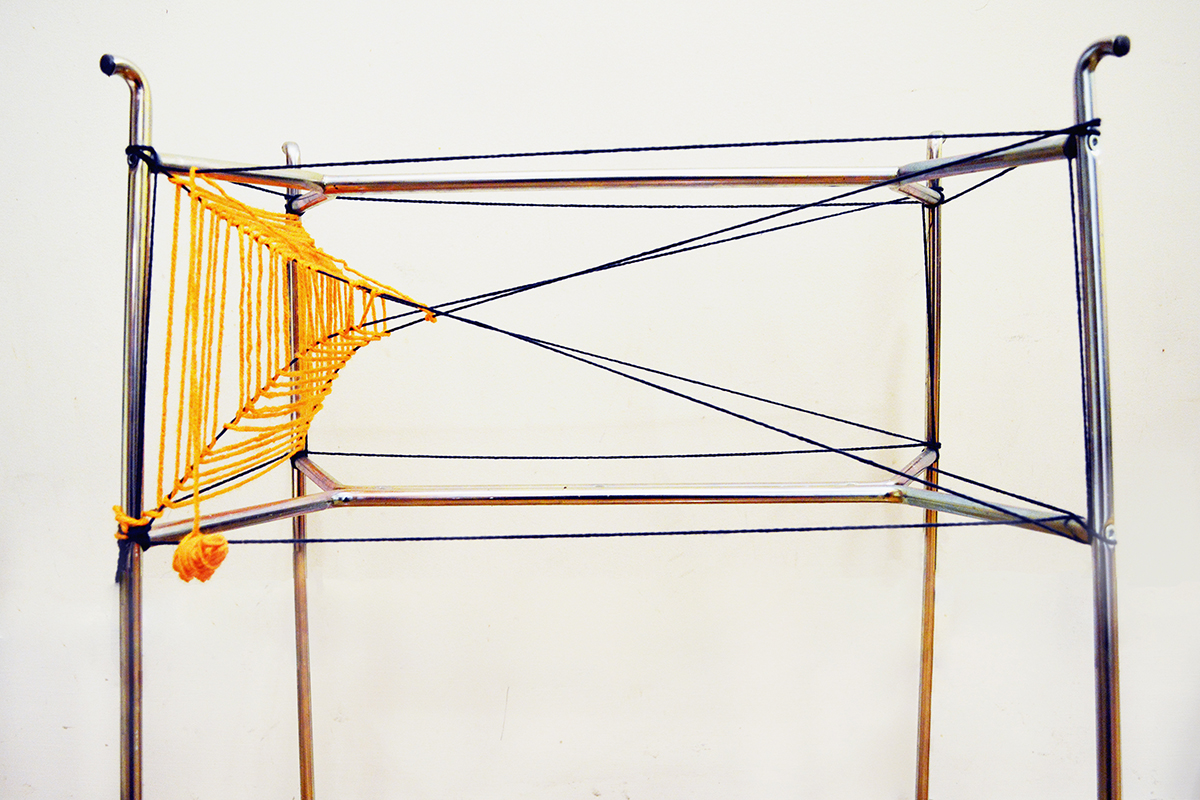

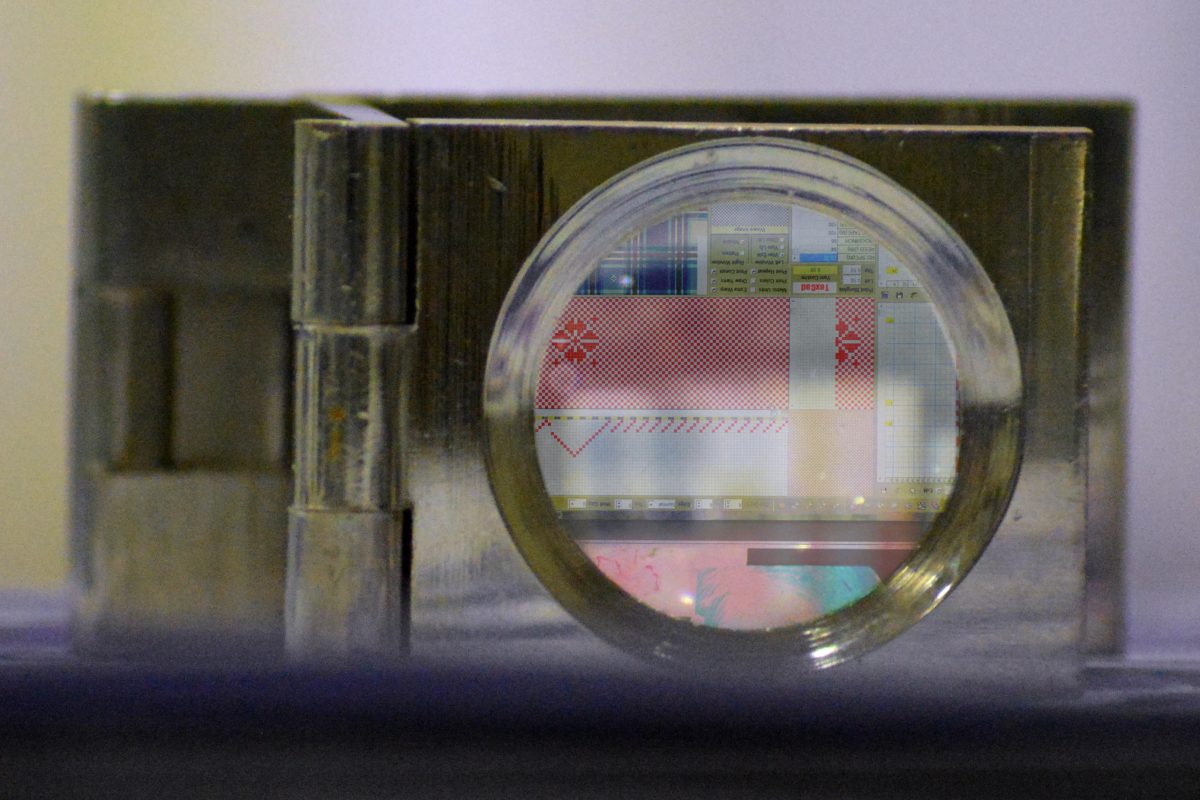

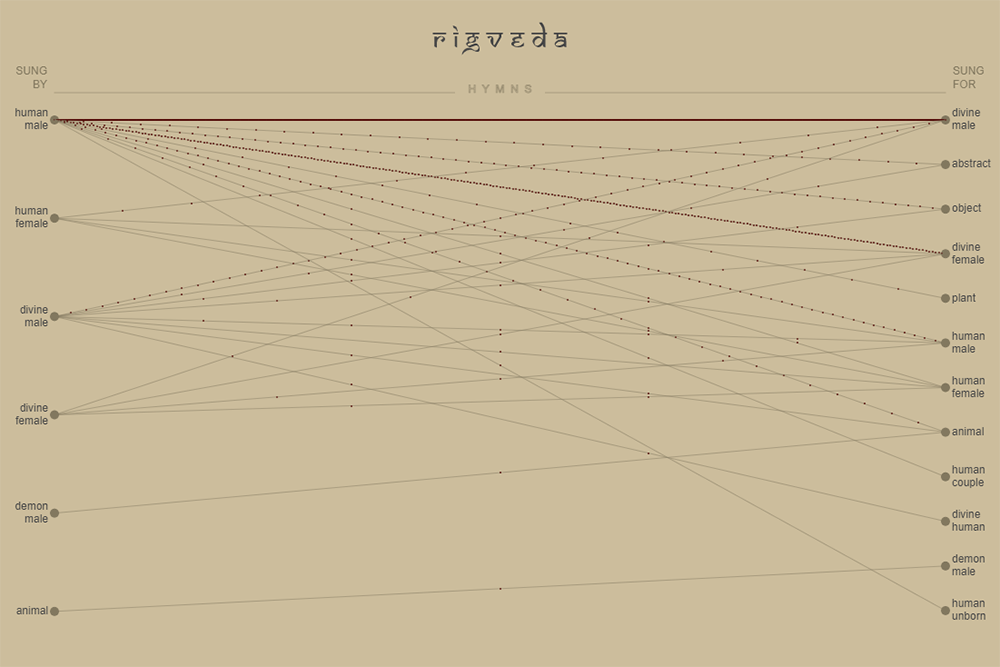

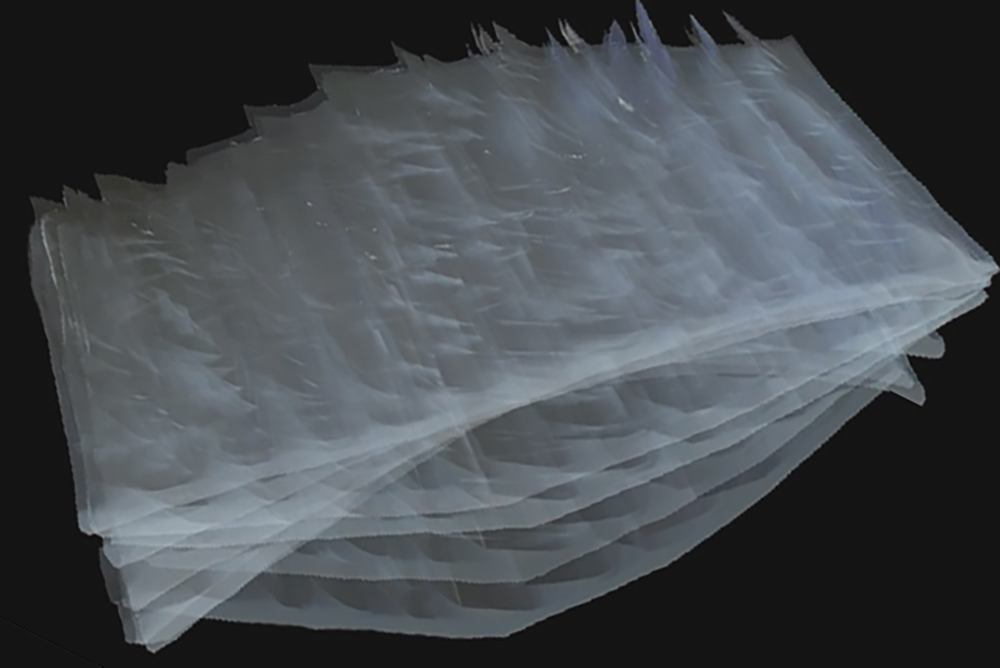

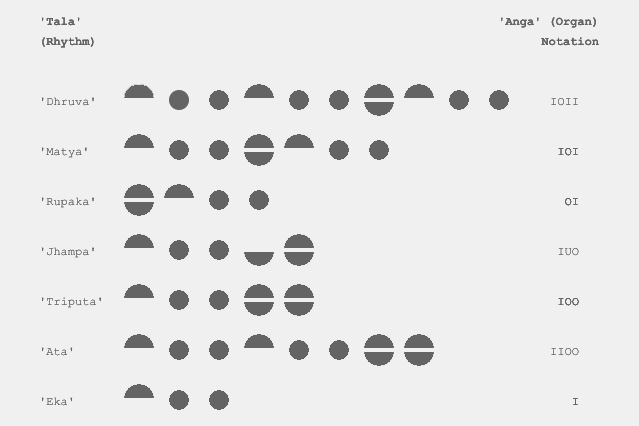

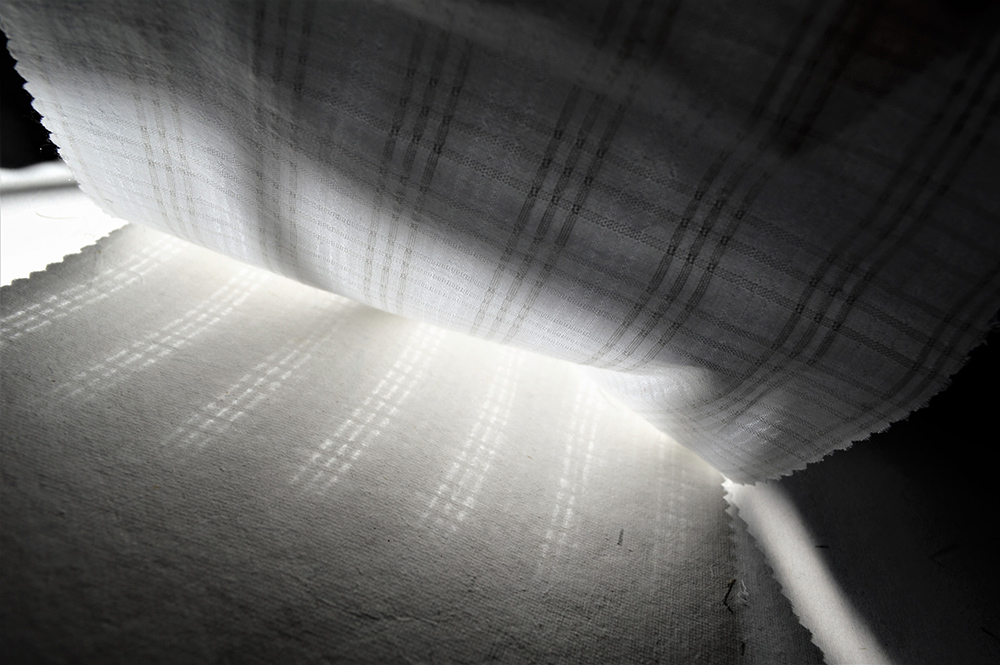

Weaving Time

2022

What is it like to experience time and temporalities through weaving?

15 min read

Published by Echoes ➚ (Design and Technology 2022 Thesis Show) ➚

Role: Author

Why do you weave a garment so gay? . . .

Blue as the wing of a halcyon wild,

We weave the robes of a new-born child.

Weavers, weaving at fall of night,

Why do you weave a garment so bright? . . .

Like the plumes of a peacock, purple and green,

We weave the marriage-veils of a queen.

Weavers, weaving solemn and still,

What do you weave in the moonlight chill? . . .

White as a feather and white as a cloud,

We weave a dead man's funeral shroud.

-[Indian Weavers, by Sarojini Naidu]

- [Alfred North Whitehead in ‘Science and the Modern World’]

- [George Kubler in ‘The Shape of Time: Remarks on the History of Things’]

What does one understand by participation? Who has agency over the fabric of time?

- 1. Albers, Anni; On Weaving; Princeton University Press; 1935.

- 2. Crawford, Matthew; Shop class as soulcraft; The Penguin Press; 2009.

- 3. Fabian, Johannes; Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object; Columbia University Press; 1983.

- 4. Kojève, Alexandre; Introduction to the Reading of Hegel: Lectures on the Phenomenology of Spirit (English); Basic Books; 1969.

- 5. Koselleck, Reinhart; Sediments of Time: On possible histories; Stanford University Press; 2018.

- 6. Kubler, George; The Shape of Time: Remarks on the history of things; Yale University Press; 1962.

- 7. Sennett, Richard; The Craftsman; Yale University Press; 1943.

- 8. Zerubavel, Eviatar; Time Maps: Collective Memory and the Social Shape of Past; The University of Chicago Press; 2003.