SELECTED

FABRICATION

STRATEGY

WEB-DESIGN

ANIMATION

SHOWCASE

GRAPHICS

DATA-VIZ

TEACHING

WRITING

ALL

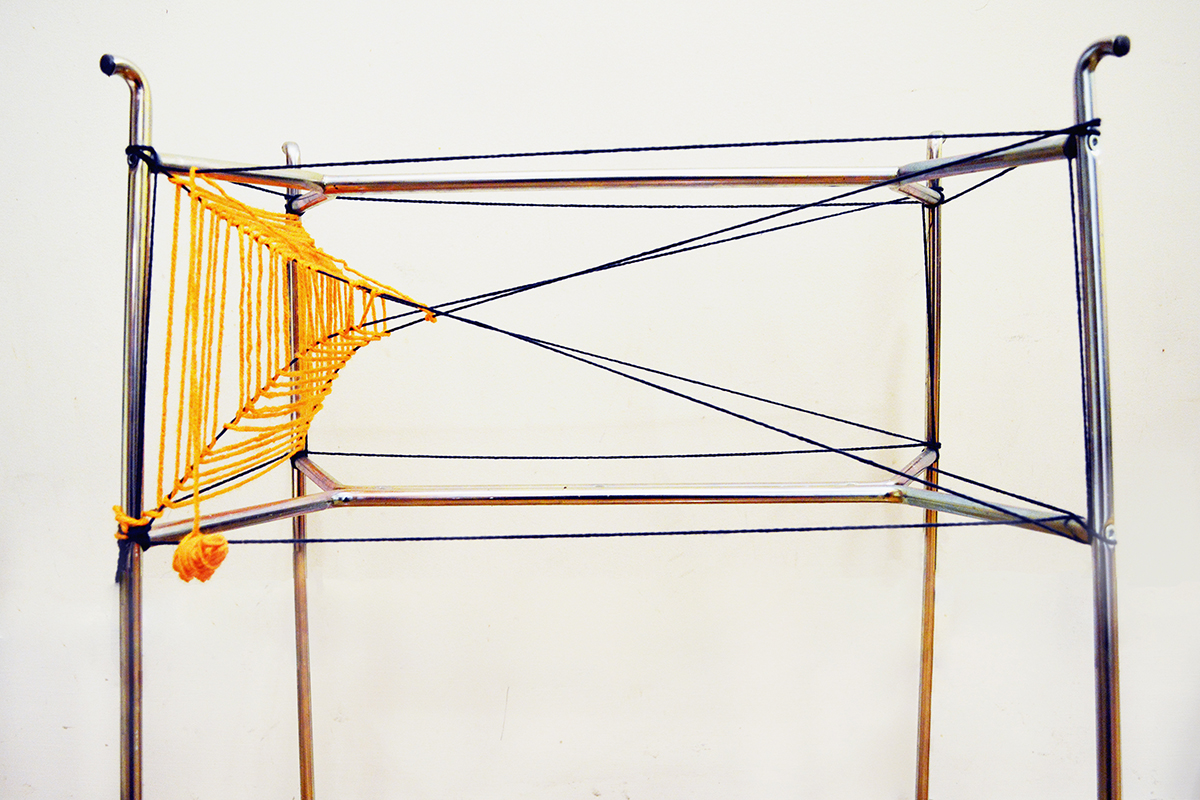

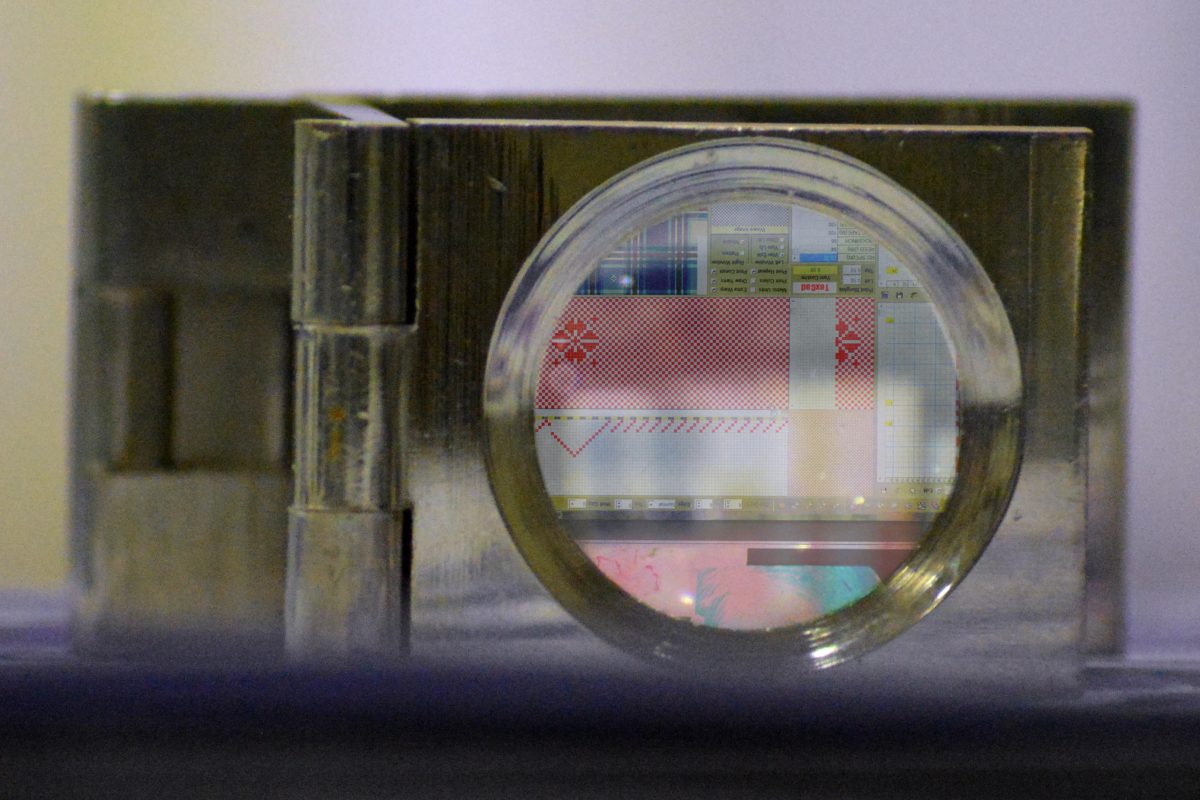

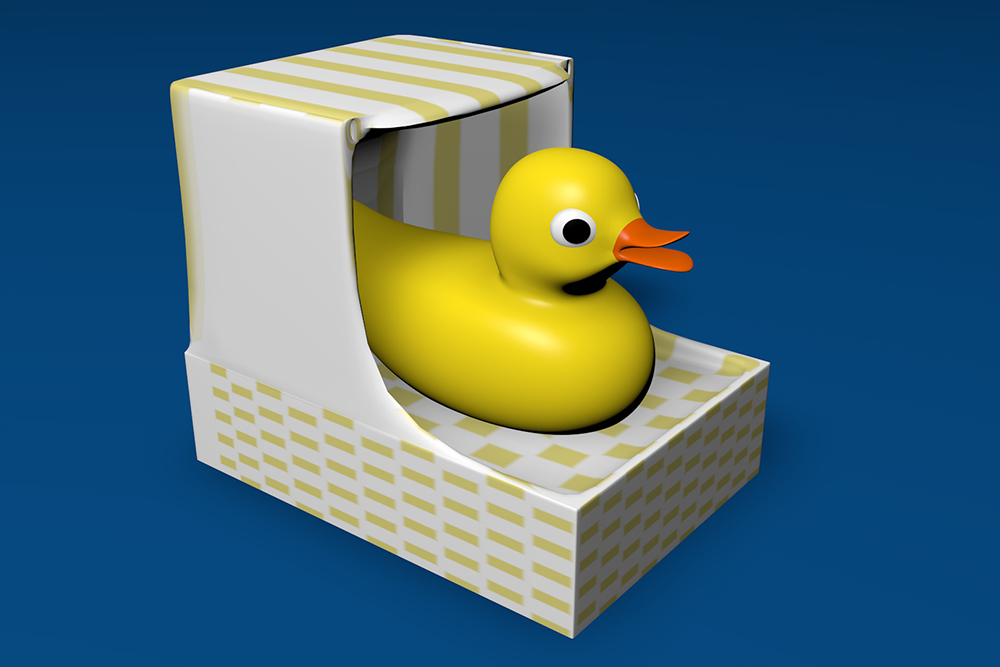

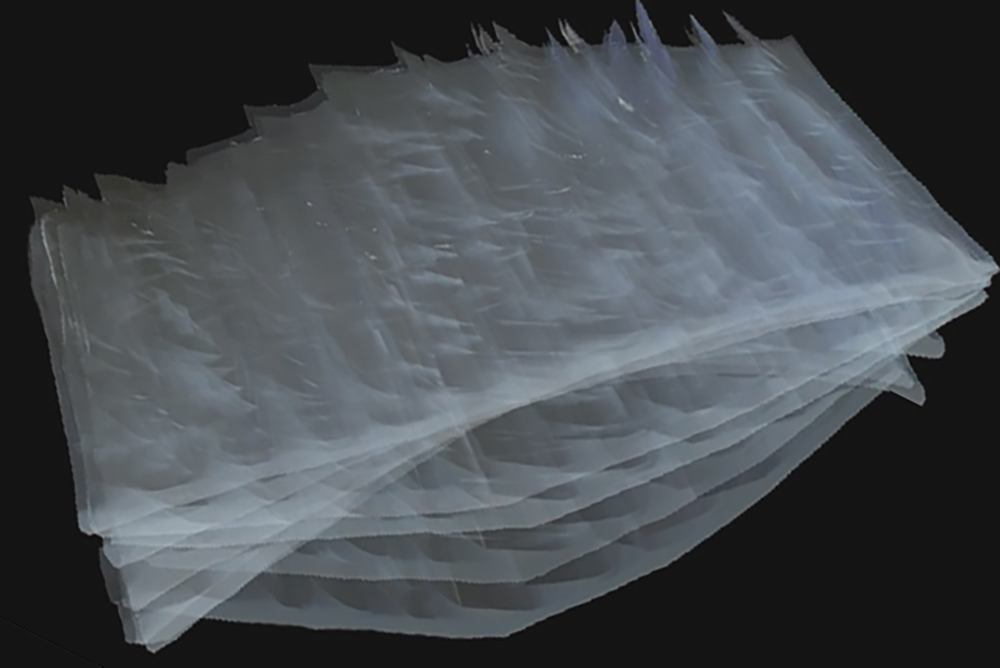

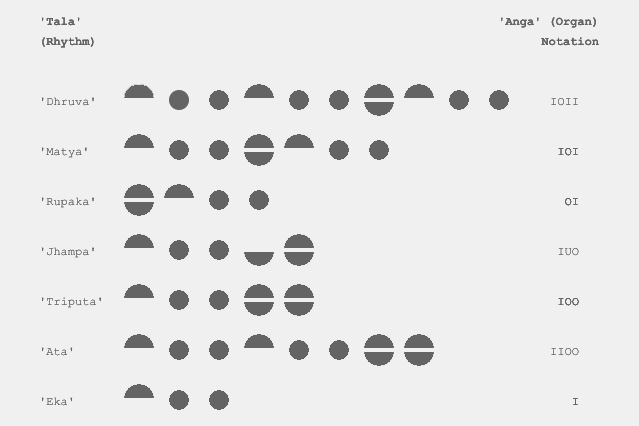

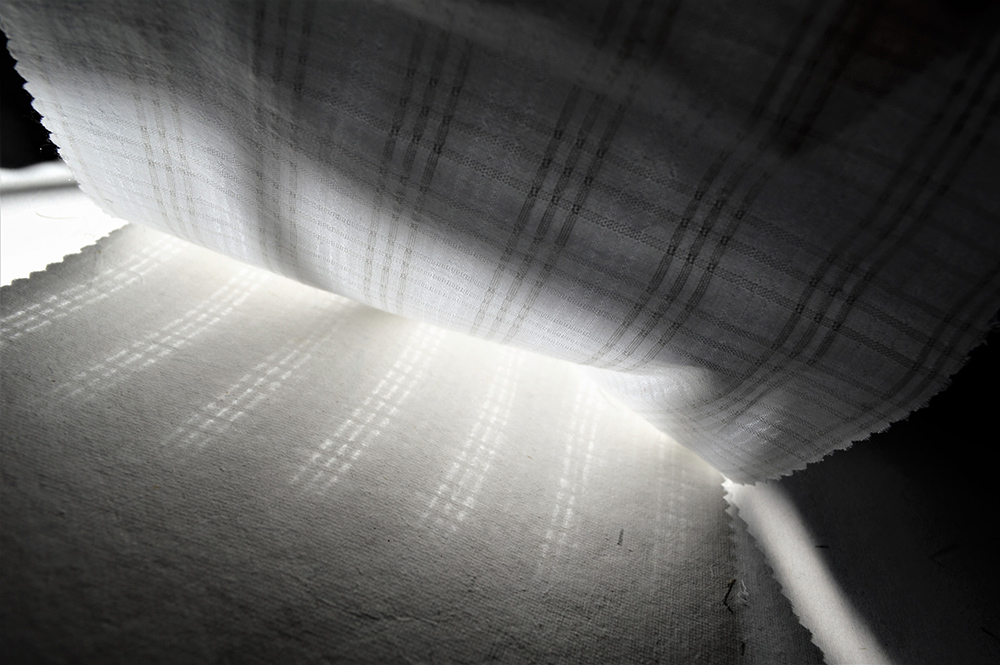

Materiality of Time: Wonderings

2022

Musings about materiality of time and temporal experiences through materials

10 min read

Role: Author

-[Fabian quoting Confessions, Book XI in his book, Time and the other]

-[George Kubler in ‘The Shape of Time: Remarks on the History of Things’]

- 1. Bailey, Geoff. “Time Perspectives, Palimpsests and the Archaeology of Time.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 26 (2007): 198–223.

- 2. Barth, Fredrik. “An Anthropology of Knowledge.” Current Anthropology 43 (2002): 1–18.

- 3. Bradley, Richard. “Ritual, Time and History.” World Archaeology 23 (1991): 209–219.

- 4. Gell, Alfred. The Anthropology of Time: Cultural Constructions of Temporal Maps and Images. Oxford: Berg, 1996.

- 5. Gosden, Chris. Social Being and Time. London: Blackwell, 1994.

- 6. Gosden, Chris, and Yvonne Marshall. “The Cultural Biography of Objects.” World Archaeology 31 (1999): 169–178.

- 7. Ingold, Tim. “Materials against Materiality.” Archaeological Dialogues 14 (2007): 1–16.

- 8. Ingold, Tim. Perceptions of the Environment: Essays in Livelihood, Dwelling and Skill. London: Routledge, 2000.

- 9. Lucas, Gavin. The Archaeology of Time. London: Routledge, 2005.

- 10. Robb, John. The Early Mediterranean Village: Agency, Material Culture and Social Change in Neolithic Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- 11. Robb, John. “Time and Biography.” In Thinking through the Body: Archaeologies of Corporeality, edited by Y. Hamilakis, M. Pluciennik, & S. Tarlow, 145–163. London: Kluwer/Academic, 2002.

- 12. Robb, John, and Timothy R. Pauketat. Big Histories, Human Lives: Tackling Problems of Scale in Archaeology. Santa Fe, NM: SAR Press, 2012.

- 13. Robb, John. The Oxford Handbook of History and Material Culture. 2020.

- 14. Shryock, Andrew, and Daniel Lord Smail. Deep History: The Architecture of Past and Present. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2011.

- 15. Tilley, C. The Materiality of Stone. Oxford: Berg, 2004.